First, you need to understand that Brian and I have a parasocial relationship that goes way back. After college, I attended a very small Reformed / Acts 29 plant church. As much as I enjoyed the sense of community I found there, I chafed against the theology that was taught (very Theo-Bro if you know what I mean). God as ready to damn and smite the sinners; us as selfish, wayward humans continually warring against God; the need to repent and continually sanctify our lives to be good enough for this God.

I was lonely that year, as I had been for much of my life. Lonely in the social sense to some extent, but more so existentially: I was constantly wrestling with faith and doubt and issues of meaning, and had almost nobody to talk to about it. I started a blog that I named “Most of My Friends Are Books.” I felt the closest to the authors I read from at this time: Anne Lamott, Rob Bell, Henri Nouwen… and Brian McLaren.

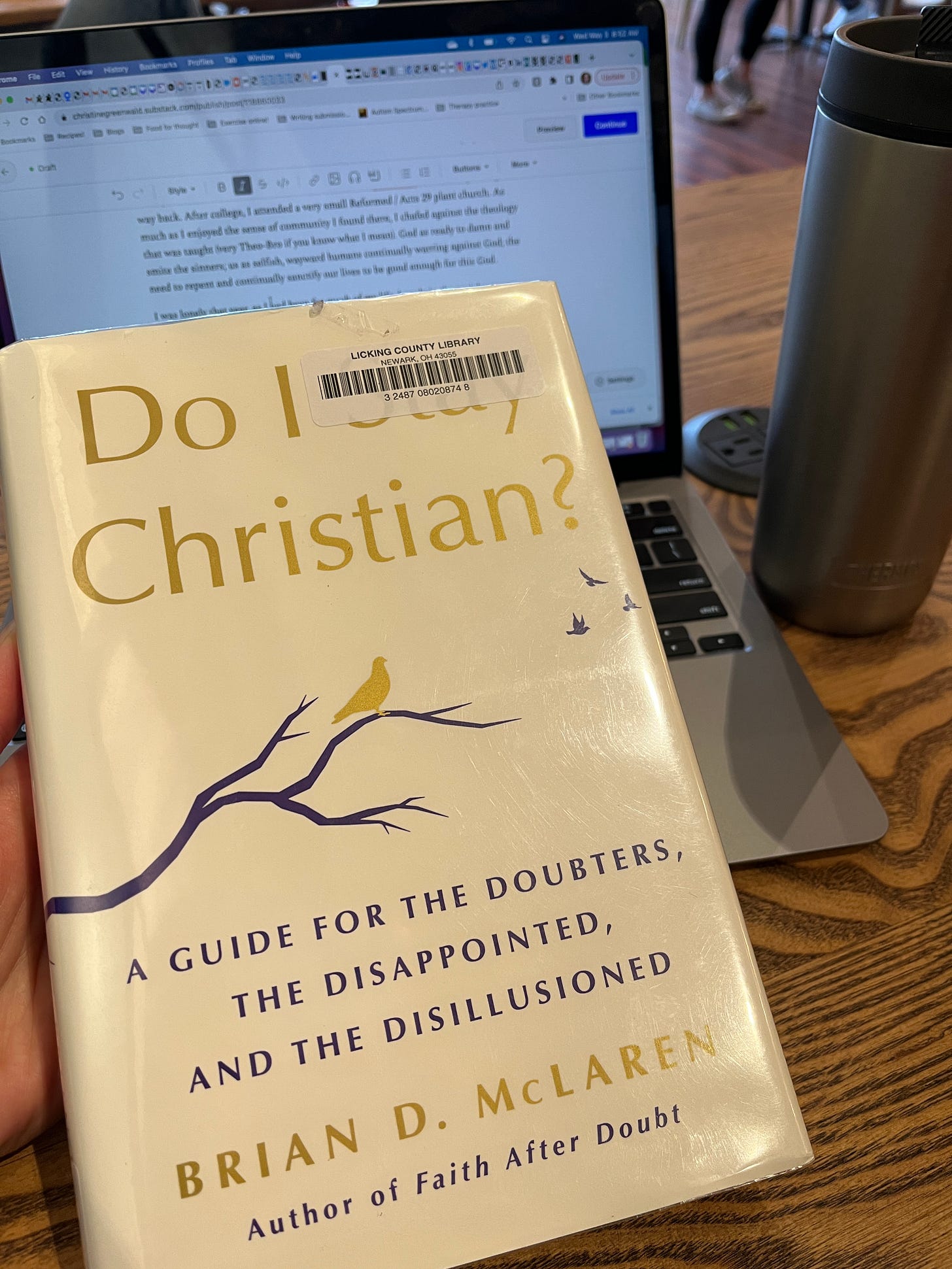

McLaren has been a much-needed companion on my journey and I’m grateful for it, and he did not disappoint with his latest book. (But maybe I’m biased from past experience).

The book is structured in three parts: part 1 is “No,” about all the reasons why (from the title) one should not stay Christian. Part 2 is “Yes”: self-explanatory. Part 3 is “How,” which addresses the question of how we live, whether or not one stays Christian. How do you make the choice in a “good, honest, and loving way?” (p. 7).

Part 1, “No,” is filled with points that readers of this newsletter and others who have experienced religious trauma are probably quite familiar with. Christianity’s violence, antisemitism, colonialism, patriarchy, anti-intellectualism…the list (and chapters) go on. Honestly, I skimmed this section because I didn’t need more convincing of what I’m already aware of. This section did bring some perspective that, as awful as conservative Christianity has been acting recently in the U.S. with its ties to the extremist Republican party, it’s had some even more awful iterations in the past. And yet somehow it has survived. Why? Why would a religion that’s done such harm keep going?

So, it was the “yes” questions in Part 2 that I was far more curious about. At this point, with the extremely tattered and worn cloth that I call my faith and spiritual journey, what could someone say that might convince me Christianity was worth belonging to? Evangelicalism got a hard hell no; never again. But as passionate as I am about that, I also passionate that ex-evangelicals cannot center evangelicalism so much as to think it represents the whole of Christianity.

But even outside that… what’s the point? Why belong to religion at all? If you get to a place where there is no hell to be saved from, and no need to believe or belong in certain ways to guarantee your eternal future… what is the point of religion?

Perhaps this is a particularly Christian, and even more so evangelical, question. I was raised in a religion that emphasized that the entire purpose was escaping the wrath of God to spend eternity with the same God who would have smited you if you had the wrong beliefs. The whole point was heaven, or the corollary, escaping hell. Not believing in hell was anathema because that would give people free license to leave the religion.

But I also recognize not all religions operate this way, and I am playing out the same narcissistic viewpoint of evangelicalism to assume this is the case. Hinduism, Buddhism, and Sikhism all believe in reincarnation. In Buddhism, for instance, the goal is to eventually escape the cycle of life, death, and rebirth (called samsara) by attaining enlightenment and reaching nirvana.

I appreciate that Brian assumes that hell is not a valid reason to belong to religion, and that having correct dogma is absolutely besides the point. He’s digging deeper and asking the questions I really care about, too.

One of my favorite chapters was in the “Yes” section about Fermi’s Paradox and the Great Filter. I guess I like a good thought experiment. I had no idea what these ideas were, so I’ll sum it up for you: Fermi’s Paradox asks why we have not been visited by other intelligent forms of life in the galaxy, running on the assumption that we can’t be the only intelligent species that has evolved. And the answer of the Great Filter responds that perhaps intelligent life always self-destructs before it can manage intergalactic travel. “Perhaps what we see happening to us on earth —that our technological evolution has outpaced our spiritual or moral evolution—has happened to every other species" (p. 150). And he asks: “Have we reached the Great Filter?”

Brian names throughout the chapter how he’s not looking for an evacuation-plan gospel, an inerrant Bible, a comforting spirituality, or a theology that provides security of an in-control god. But he does need a spirituality, a Jesus, and a worldview that transforms him and reminds him that “the whole universe is filled with a spirit (or Spirit) that is brooding, gestating, laboring becoming, yearning, learning, reaching…” (152).

I have no real respect for a book that asks the question “Do I stay Christian?” and offers only one correct answer (which would be yes), much like the dogmatic books of evangelicalism would do. But that’s not the sense I got from Brian’s book (154-5):

To some degree, we must all hold both options in tension: Will we stay Christian? and Will Christianity survive? are less important questions than these: How shall we humans survive and thrive? What good future shall we strive for? How can we align our energies with the divine energy at work in our universe? That striving, that pursuit, that transformation project is bigger than Christianity and bigger than not-Christianity.

At some point, the question of religion or no becomes irrelevant. It’s more a question of “what are we doing with this one life, and one world, that we have?”

When I went to seminary in Indianapolis (as opposed to my 13k pop town here), I had the opportunity to go to a lot of interfaith events. I got to learn from Muslims, Jews, Sikhs, Buddhists, Unitarian Universalists, and more. The thing that struck me most was that the progressive branches of each of these religions have far more in common with each other than they seem to have with the conservative branches of their own religion.

And why should the conservative / fundamentalist branch be the one that gets to define what the religion is?

I wish there was some way to align myself with the many people of these various progressive, humanistic branches of religion without having to ascribe to the beliefs of one of them in particular. (Or is that cheating?) A way to say “I also believe in the potential of humanity…of our individual and collective ability to do good in the world…of the validity of seeking something beyond, of engaging in spiritual practices.”

It’s like spiritual-but-not-religious, but also sort of religious, because I’m leaning on the network that’s been created by religion in my quest for community and solidarity in these efforts.

And it can look unexpected: like right now, I meet with a church group that gathers Sunday mornings in a gay bar. They are defined by the Anabaptist tradition of nonviolence, something that aligns with my own heart. And I don’t have to sign any doctrinal statement to keep showing up and having me and my kids be faithfully loved.

So. Now that I have answered the titular question “Do I Stay Christian?” in a crystal-clear way (HAHAHA), what are your thoughts? (If you’ve been following closely you know that I’ve used the phrase “church-adjacent non-Christian” to describe myself, which still fits. But it also feels like a messy answer to “do I stay Christian?” The answer being no…but also kind of?)

I might do one more post in this vein about how no matter where we go, we will find the same problematic elements of humanity in the groups — and that the inner work we must engage in is vital for changing the world. But this is enough for today, I think!

Hi there, ex-high-control-religion support group! Where have you found yourself in this Yes / No / How journey? What are your feelings toward religion - the specific one you came from, and/or religion in general? Do you feel a need to answer the Yes / No / How question of whether to stay Christian (or religious at all), or are you comfortable in the unknown, the messy middle? See you in the comments!

I think it’s true that groups will always have their difficult dynamics, and that inner work by individuals is crucial for growth, whether that be spiritual or any other kind. One thing I struggle with is how people go to church and expect that that is going to do the Internal work for them, not unlike people coming to therapy and expecting (and hoping and praying) that the therapist is going to do the work. I also admit to being church-adjacent in that there is a lot of amazing work by composers that I wouldn’t have gotten to engage with if I had stayed unwilling to enter a church. But wow, is there baggage. At this point in life I’m accepting of living in the struggle without clear answers. I try to be gentle with others and hope they are gentle with me. And the journey continues, and continues to change. I am glad we’re all here together!

I really appreciate all your thoughts here, Christine. I've been trying to find safety from that same theo-bro, violent-God theology for a long time. While I was running away from toxic theology and exploring a lot of different options, I finally stumbled to a place I think I can stay. I'm staying Christian, but only because I'm starting to look at the Bible through an interpretive lens that actually takes seriously verses and promises that the Reformed tradition overlooks or explains away because of their theological filters. Passages like Isaiah 25:6-9, Rom 5:15-19, 1 Cor 15:28, Col 1:19-20, and one of my lifetime favorite verses, 1 John 4:18. I've learned to trust my instincts that if God is real, God has to be good and has to be love, and there is no fear in love. I've learned that salvation is not being saved *from* hell or punishment, but being set free *by* Jesus from captivity to sin and death, and saved *for* abundant life in God. Of course, I'm still figuring things out on this journey, but, I've been reading David Bentley Hart, and listening to a lot of other podcasts and sermons, and exploring early church fathers who believed in the ultimate reconciliation of everyone to God, and finding out, like you wrote in your post on hell, that the idea of an eternal hell wasn't even invented until the 4th century. To sum up, I've started to see things much like you wrote in this post: that the "point" of Christianity is not to see who goes to heaven or hell when they die. It's to be with God, know God, and labor with God here and now as he's reconciling the world to himself.